Humidity, spider webs, bear scat: all can be found in eastern Kentucky deep into summer. And despite these things, the sentiments expressed around fieldwork for geographic research include: “Fieldwork is why we do what we do!” “I can’t believe we get to hike around for the sake of research and call it our job!” “Fieldwork helped me feel like a researcher, a student of the world- not just the university.” Fieldwork in geography is unequivocally diverse, whether it is interviewing farmers in Vietnam, or estimating vegetated groundcover below chest height in Appalachia, or observing traffic at an intersection in Louisville.

Woolly adelgid live on hemlock tree branches.

A large hemlock tree affected by woolly adelgid.

I was lucky enough to join graduate student Grace Embree in collecting data for her thesis in late July tracing the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid outbreak along natural and protected areas on Pine Mountain. Hemlock trees, known as the redwoods of the East, are a staple evergreen tree in the mixed mesophytic forest. The woolly adelgid, introduced in the mid-twentieth century, is a tiny insect that sucks out the sap of hemlock trees and can consume an entire tree’s nutrition over the course of a few years, leaving the trees without their needles and ultimately dead. While there are many efforts to treat these trees before an infestation takes their lives, it is still uncertain how extensive the damage may be to our Appalachian Mountain forests.

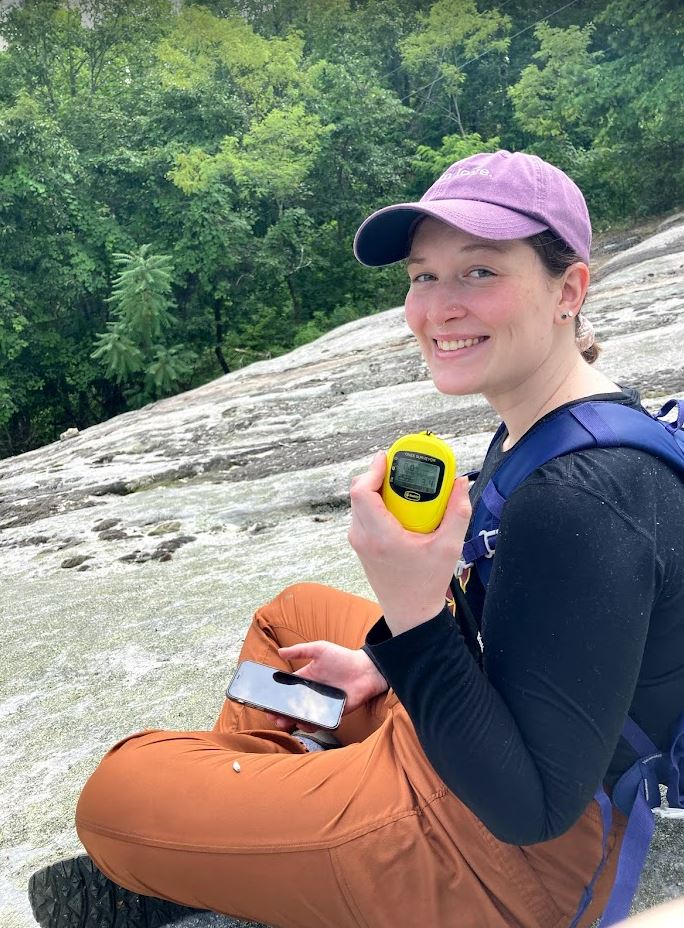

Grace poses with the Bad Elf GPS unit.

A densiometer in action capturing the ratio of sunlight to canopy cover.

Each time Grace and I set out, saddled up with maps, water, the Bad Elf, a densiometer, and bug spray, we hiked existing trail networks to find the randomized points generated in ArcGIS Online in the Field Maps App. These random points represent Grace’s training data and become very important as she works to characterize the health of hemlocks all along Pine Mountain using satellite imagery! As we approached each point, we measured an accurate position using GPS technology (Bad Elf!), captured photos and tree health attributes (looking for needle loss and signs of infestation), and estimated tree canopy density using (you guessed it) a densiometer.

Each evening back at Lilley Cornett Woods Appalachian Ecological Research Station, where we stayed with the generous support of Eastern Kentucky University, we backed up location data and photos from our devices to the online databases and a laptop. We cooked dinner, chatted with Curtis the property manager, and read about the other fascinating research hosted at Pine Mountain and many of the protected old-growth forests in eastern Kentucky.

Over the course of three days, we were able to gather 35 sample points, spanning about 18 miles of trails, at the Pine Mountain Settlement School and Kingdom Come State Park, both of which offered views of the hazy summer Appalachian hills. It was at the top of Pine Trail at Kingdom Come State Park that Grace exclaimed, “I can’t believe we get to hike around for the sake of research and call it our job!” With the light peeking through the rhododendron onto my face, I couldn’t agree more!

For now, it’s back to the lab for Grace and me- for her, to develop a remote sensing model derived from ground truth points and satellite imagery; for me, to develop a fieldwork manual for students, support GIS research across the university, and write this reminiscing post! Though, my guess is that you will find any of us back in the field as soon as possible- whatever and wherever the field may be.

Author Laura Krauser is the GIS Research Coordinator at the University of Louisville Center for GIS, and can be contacted via email at laura.krauser@louisville.edu.